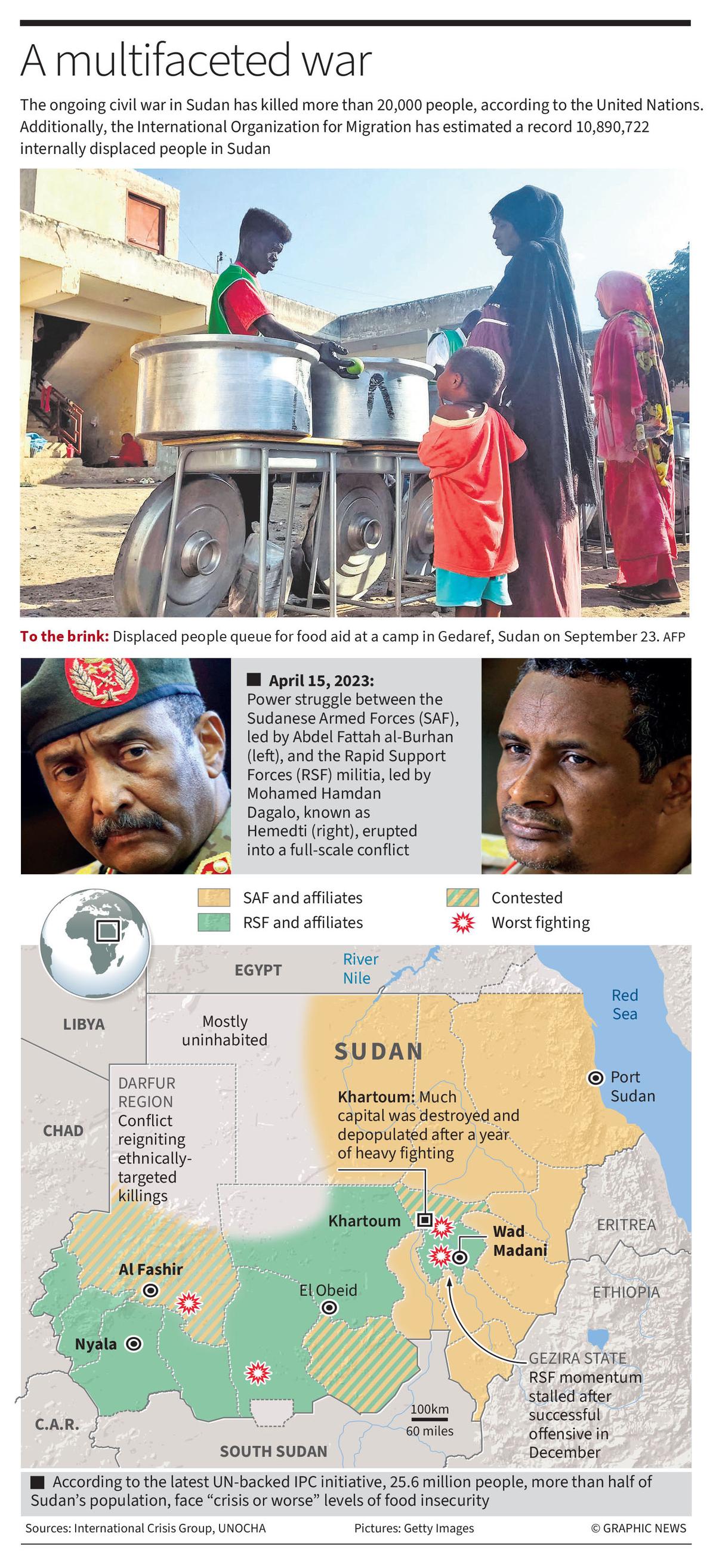

The story so far: On September 26, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) launched a major offensive against the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Khartoum and Bahri. Thus, the war which was quiet for a few months has gained momentum again. Eighteen months into the civil war, the UN said that more than 20,000 people have been killed. Additionally, the International Organization for Migration has recorded an estimated total of 10,890,722 internally displaced persons (IDPs) as of October 1. All ceasefire efforts and peace talks have failed so far. The latest offensive comes ahead of the U.S.-led ceasefire talks on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly.

Also Read: Why is Sudan still at war a year on? | Explained

Who are the actors in the civil war?

The civil war in Sudan between two military factions, the SAF and the RSF has crossed 18 months. It started as a power rivalry between the military heads of the SAF and the RSF, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Hamdan Dagalo respectively. What began as a conflict in the capital city of Khartoum has spread to Omdurman, Bahri, Port Sudan, El Fasher and the Port Sudan cities, as well as the Darfur and Kordofan states.

The RSF has an upper hand in multiple war zones. However, since August, the SAF has been carrying out frequent airstrikes and has captured pocket regions around Khartoum. The humanitarian crisis is worsening countrywide amidst limited and restricted access to aid and health care, especially in the Darfur states. The warring sides are also accused of carrying out war crimes including sexual violence and extrajudicial killings in several regions. In August, the UN declared famine in the Zamzam camp in North Darfur which hosts nearly 5,00,000 IDPs. The UN- Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) Famine Review Committee says that 14 regions in the Greater Darfur, South and North Kordofan, and Jazeera states face conditions similar to Zamzam. According to the latest UN-backed IPC initiative, 25.6 million people, more than half of Sudan’s population, face “crisis or worse” levels of food insecurity. Conditions have further worsened amidst heavy rains and floods and the subsequent spread of cholera. The outbreak has killed more than 200 people.

Why is the war continuing?

There is no sign of an end to the war. Firstly, both warring parties are adamant about gaining ground and legitimising their power. The SAF claims to be the legitimate government, with the UN just about recognising their claims, although it came to power through a coup in 2021. However, the RSF has territorial gains around the capital and other war zones. It opposes the SAF’s efforts to represent Sudan internationally, claiming legitimacy. The RSF, a former Arab militia known as Janjaweed, seeks alliances from several Arab countries to support its claim to power.

Secondly, Sudan has been under the UN arms embargo, since the 2004 Darfur crisis, which has recently been extended for another year. However, the embargo has not blocked the flow of weapons. A Human Rights Watch report in July claimed that the warring parties have been using armed drones, drone jammers, anti-tank guided missiles, truck-mounted multi-barrel rocket launchers, and mortar munitions produced by companies registered in China, Iran, Russia, Serbia, and the UAE. Easy weapon procurement and use have aided the continuation of the war.

Also Read: Nearly eight million displaced by Sudan war: United Nations

Thirdly, the war has become complex with the involvement of multiple actors and issues. What began as a military rivalry has now evolved through ethnic lines, involving several regional ethnic militias. Arab and non-Arab militias have taken sides with the RSF and the SAF respectively. The rebel group Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement has been fighting alongside the SAF. The RSF and its allied Arab militias have been targeting the Masalit community and other non-Arabs in Darfur states. Ethnic tensions have intensified the war.

Fourthly, the SAF has accused the UAE and previously Russia’s Wagner Group of supporting the RSF. Although the Wagner group and the RSF have rejected any direct military engagement, the group is allegedly supporting the RSF by facilitating the supply of UAE’s weapons through the Central African Republic. At the same time, Russia has been supplying weapons to the SAF as well. With abundant external support, both parties have little motive to end the war.

Have there been peace talks?

There were nine rounds of ceasefire efforts led predominantly by the U.S. and Saudi Arabia; all failed in their primary phase. On August 14, the latest round of U.S.-led peace talks were held in Geneva, Switzerland. But, neither of the warring parties attended. SAF boycotted the meeting, blaming the RSF for not adhering to the Jeddah Declaration 2023, including the withdrawal of forces from civilian regions. RSF also pulled out from the talks at the last moment.

The UN, the African Union, the U.S., the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, and the EU have all urged the parties to end the violence and work together to de-escalate the crisis. Egypt initiated a draft resolution on May 1 at the Arab League meeting in Cairo, calling for an “immediate and comprehensive cessation” of hostilities. Until now, any and all efforts at a long-lasting ceasefire have been ineffective.

The RSF and the SAF claim they are open to negotiations but have shown little commitment to comply. They attempt to gain a military advantage during the ceasefire, owing to mistrust between the parties. Both sides have not reached a possible bargaining stage for an effective mediation.

Another reason is that international media attention to the war on the ground is limited. International organisations’ access to war zones is also restricted. With a limited understanding of the conflict on the ground, mediators like the U.S. and Saudi Arabia are challenged to formulate a ceasefire or peace talk which fit the multifaceted war situation.

What are the regional implications?

More than two million people have sought refuge in neighbouring countries including Chad, South Sudan and Ethiopia. The refugee camps are overflown and have raised concerns in Europe that many will attempt to reach the continent. In February, dozens of Sudanese drowned when a migrant boat capsized along the Tunisia-Italy route. A lack of state apparatus and institutions has triggered ethnic clashes along the South Sudan, Ethiopia and Eritrea borders. Since January, ethnic violence in the Abiey region, a disputed land between Sudan and South Sudan, has increased, with the UN reporting more than 100 casualties. Frequent clashes over agricultural land are reported in the El Fashaga region on the Sudan-Ethiopia border. The war has jeopardised an oil pipeline from South Sudan to the Red Sea.

What next?

The involvement of multiple actors and extended geography has made the war complex, challenging international actors to bring the warring parties to the negotiating table.

Multiple failed ceasefire attempts and peace talks imply the need to revisit international actors’ approach to the war in Sudan. Although SAF has been gaining pockets in Khartoum, defeating the RSF is a long road. The RSF lacks international support to claim legitimacy. And, a RSF-SAF compromise is highly unlikely. The war will likely be prolonged until a major breakthrough.

There is an increasing fear that the military rivals will divide the country, leading to a plight similar to that of Libya’s. Sudanese people have started to live with the war, and with much attention given to Gaza and Ukraine, the war in Sudan will continue to rage on the sidelines.

The author is a Research Associate at the Africa Studies, National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru.

Published – October 07, 2024 08:30 am IST